On any site that uses passwords for authentication, be it Google, Facebook or this one, the site needs to have some way of telling whether the password given by the user matches the correct password. This alone is a simple concept — but at the same time we need to make sure that we protect users’ passwords if the database containing usernames, passwords, etc is compromised. Many people use the same password for different web services, so if an obscure website’s database was hacked and the emails and passwords of their users were compromised, it’s likely that more than a few used the same email and password combination for their PayPal account, Google account, online banking accounts… you get the idea.

Let’s first consider the example where we simply store users’ passwords in plaintext (that is, if a user’s password is abc123 we store abc123 in the database). Consider the following set of users.

| User | Password | Password data stored in database |

|---|---|---|

| User1 | abc | abc |

| User2 | abc | abc |

| User3 | abd | abd |

| User4 | def | def |

Obviously anyone who gains access to this database will have all the login details for all users immediately. The site owners always need to be able to tell whether a user knows the correct password, so all we can do is obscure the process of calculating a user’s password from their database data.

(Aside: encrypting the database with a secret key could be seen as a solution; however, the majority of web attacks are done through the likes of SQL injection vulnerabilities, which execute at a level at which the database can be read in a decrypted form.)

A good first step is to apply a public, well-tested hash function to the passwords in the database, and store the password hashes rather than the passwords themselves. A hash function is a one-way function; that is, is it easy to perform one way (i.e. turning the password into the hash), but hard or impossible to do the reverse (i.e. turning the hash into the password). Since hashing algorithms map to a fixed-length string, there are guaranteed to be hash collisions and so it is often impossible to know the original text given the hash. For this example I am going to use the SHA1 algorithm, which is conveniently built into many web programming languages including PHP. Our database would now look as follows.

| User | Password | Password data stored in database |

|---|---|---|

| User1 | abc | a9993e364706816aba3e25717850c26c9cd0d89d |

| User2 | abc | a9993e364706816aba3e25717850c26c9cd0d89d |

| User3 | abd | cb4cc28df0fdbe0ecf9d9662e294b118092a5735 |

| User4 | def | 589c22335a381f122d129225f5c0ba3056ed5811 |

To the human eye this would probably be good enough. Also, note that although User2 and User3 have very similar (but not identical) passwords, their hashes are completely different. (As a rule of thumb, changing one bit of data in the plaintext should flip approximately 50% of the bits of the resulting hash.) However, there are still a couple of caveats:

- Anyone looking at the database would know that User1 and User2 have the same password.

- Databases using popular hashing algorithms are still vulnerable to rainbow tables. These are huge tables holding the result of hashing every possible string, often up to a certain number of characters. For example, the rainbow table available here for

SHA1hashes of lowercase letters, numbers and spaces up to 9 characters is already 52GB! Anyone with a hash could run it through such a rainbow table and come up with possible sources for that hash.

Rainbow tables are only useful when someone has gone to the bother of generating them, which means that obscure or self-coded hashing algorithms will likely not have a rainbow table against which they can be looked up. However, such algorithms are not likely to be mathematically rigorous enough to be considered a strong hash function, which is bad news if you’re a big target like Google.

A way to protect against rainbow table attacks is to ensure that the number of characters in the plaintexts are not included in the rainbow table’s domain. For example, in the example above, the 52GB rainbow table only worked when the passwords were 9 characters or less — so anything above 9 characters would be invulnerable to this current rainbow table. And since it’s extremely low overhead to hash something as short as a string of text, we might as well add, say, 10 characters to each password. (In practice you would want to do more than this, but I want to fit everything on the page!) A common string of characters that we concatenate with every password is called a salt. Let’s take our salt as abcdefghij. Then, for example, the first entry in the database will be the result of applying the SHA1 function to abcabcdefghij.

| User | Password | Salt | Password data stored in database |

|---|---|---|---|

| User1 | abc | abcdefghij | 0143aa54b192a3db577861c54d60486920634b28 |

| User2 | abc | abcdefghij | 0143aa54b192a3db577861c54d60486920634b28 |

| User3 | abd | abcdefghij | 03c313d4f74ab4d53a7312f42ca1287938169aed |

| User4 | def | abcdefghij | 5d4b46aa07beb42a8057f1913e70e8d9e53bdbc7 |

Note that User1 and User2 still have the same stored password. While we assume that the salt will also be compromised if the database is, all existing rainbow tables will be worthless. However, if the target was high-value, a new rainbow table could be constructed to work explicitly for this database. Since the overhead of each SHA1 operation is very low, we might as well slow down any would-be crackers by performing it recursively many times, say 4096. (This is the number of rounds of hashing performed by the WPA algorithm, which takes the SSID of the access point as its salt.) This will represent no slowdown to us, but to an attacker it will slow down the creation of the rainbow table 4096-fold. We now have the following data.

| User | Password | Salt | Password data stored in database |

|---|---|---|---|

| User1 | abc | abcdefghij | 1cf0c7f82fa8dbbb3e68b96130d33b8defaf1791 |

| User2 | abc | abcdefghij | 1cf0c7f82fa8dbbb3e68b96130d33b8defaf1791 |

| User3 | abd | abcdefghij | 63480fa579f5a067db0254771ba13bdc6534503b |

| User4 | def | abcdefghij | 9a19325b82d0a8d6a3748c71d6e4d767e4a3fb14 |

We still have the problem that User1 and User2 can be identified as having the same password. So, as well as having the database-wide salt to obscure our data from rainbow tables, we add a pepper to obscure each entry from each other. (In practice, an attacker would have to create a separate rainbow table for every entry they wanted to crack!) With the peppers listed below, we now have the following final data.

| User | Password | Salt | Pepper | Password data stored in database |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| User1 | abc | abcdefghij | qwertyuiop | e27cb9a5f3973a5d173f6d5da95565ca668f3fea |

| User2 | abc | abcdefghij | asdfghjklp | b0c8d626936e30a7b7561be5ad4384e43454ab04 |

| User3 | abd | abcdefghij | zxcvbnmkop | 7ed2c4d59f006c5d321f653cb1a98ec8cf8e6a8d |

| User4 | def | abcdefghij | 1q2w3e4r5t | 265f5ac148f1242c8af4ee2e70dcbe077519a3f7 |

And now we finally have our solution! The same plaintexts now hash to different values, as their individual peppers are different.

There are some additional measures we could take to increase the security of the system as a whole.

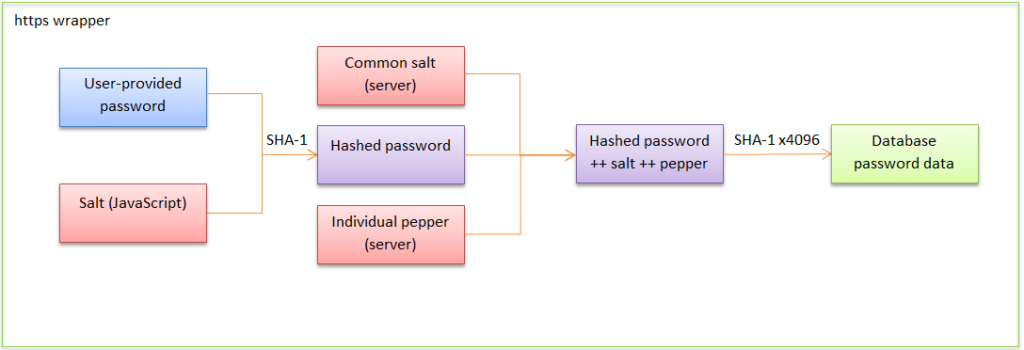

- Hash the user’s password client-side using JavaScript or similar so that the server never “sees” the original password. This will prevent a passive man in the middle attack. (While we’re at it, we may as well salt the hash.)

- Use a session-encryption technology like https. Such a technique is required to prevent active MITM attacks, as additional layers of JavaScript will only provide obscurity rather than security if an attacker can change a page’s or script’s content in transit to the user.

If the above wall of text proved difficult to follow, the process is pictured below.

The site owner would take the data provided by the user, run it through this process, and compare the result with the data stored in the database. If they match, the password the user originally entered must have been correct. All this can be done by the owner with absolutely minimal computational overhead. Are you paying attention, Sony?